Read for Empathy 2024: Librarians' Blog

- By EmpathyLab

- •

- 29 Feb, 2024

- •

Hear from two Librarians who judged the 2024 Read for Empathy collection

The collection consists of 65 books for 3-16 year olds, each chosen for its unique contribution in building young people’s empathy.

The primary collection for 3-11 year has 40 books; the secondary collection features 25 books for 12-16 year olds.

Bigger empathy questions such as the environment are addressed in Hannah Gold’s Finding Bear. In Grandpa and the Kingfisher Anna Wilson and Sarah Massini use nature’s life cycles to help children deal with the fear of death of loved one.

The secondary collection covers subjects new to the Read for Empathy collections which have been annual since 2017. Crossing the line by Tia Fisher has a central character caught up in county lines. It’s not an easy read, but it gives the reader piecing insights into the experience. SOLD: What will it take to find freedom? by Sue Barrow with illustrations by Jennette Slade is about human trafficking and how difficult it is to escape.

Two novels that stand out for their powerfully drawn heroines are Hazel Hill is gonna win this one by Maggie Horne which explores misogyny. The central character in Sing if you can’t dance by Alexia Casale refuses to be defined by her disability and takes on the bullies with great one liners. The detailed descriptions her crippling illness make the reader wince empathetically.

The Piano at the Station by Helen Rutter and Elisa Paganelli is vitally important, making us think about how young people are being missed by those who could help. While the Headteacher in Lacey’s school does recognise she needs help, Lacey is fighting a chaotic home life, just one voice among a large family with little money. Nicola Davies and Petr Horáĉek have produced a beautiful poetry book Choose Love which deserves time despite its apparent simplicity.

As well as the book collection, EmpathyLab offers training for teachers and library staff. A modular course is supported by resources to help to build children’s empathy, literacy skills and social activism. They can act as a foundation for progressing to become an EmpthyLab Affiliate School. Details here: https://www.empathylab.uk/our-foundation-empathy-programme

Use of books in libraries

Many library authorities order and promote the Read for Empathy lists. Schools too will use the lists to fill gaps to help support their students, some schools having had experience of all these situations at some time. The books will show young people who have lived through this reality they are recognised, and if others know their situations, they can’t help but be moved by the characters’ experiences.

I am very fortunate to have been on the Read for Empathy booklist judging panel over the past few years.

I’m also a practising classroom teacher so I would like to consider how the books on the list can influence what happens in a school.

Firstly, along with many other schools, reading aloud is an important part of our school day, every day, almost without fail. All the teachers at my school are aware of the EmpathyLab booklist, and often use it as a basis for choosing their next class read. Knowing that the books touch on important aspects of our children’s lives is key; we all understand how important representation is in stories. These are books that make a difference, that lead to passionate discussions in the classroom and can actually influence children’s behaviour .

The booklists become increasingly valuable. We have a couple of hundred empathy texts at our school – they are there on merit. Staff often refer to previous lists if there as a particular aspect of empathy that they want to include or share with the children.

Our Year 6 Reading Champions often seek out picture books from the list to take in to KS1 and Reception when they read stories, so we already have the next generation educating each other about the importance of empathy. I love the fact they often meet beforehand (they tend to work in twos) to discuss what questions they might want to ask the children once the story has been read. After each booklist is released, they also spend several of their Friday recommendation slots in assembly talking about a couple of the books. We have parents in on our Friday assembly so it’s a great way to share the texts with them and help raise their awareness of our work.

We often use the books as our teaching texts for English, partly because they encourage excellent writing but also because they provide a fantastic opportunity for our pupils to develop their empathy skills. The Wild Robot by Peter Brown, Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane by Kate DiCamillo, Freedom by Catherine Johnson, Eyes that Kiss in the Corners by Joanna Ho and A Street Dog Named Pup by Gill Lewis are all books that have made in into our English curriculum as a result of being on one of the Read for Empathy booklists. Well, that’s not strictly true - Edward Tulane was there before that as it’s one of my favourite ever books, but you hopefully take my point.

Reflecting on our empathy journey over the past few years, I’ve also found that the more books children read that address empathy, where they can relate to the characters and their choices, the more books they want to read. It’s almost a virtuous circle. Many begin to realise that such books can empower them to think about situations.

For example, as soon as we finished A Street Dog Named Pup last year, several of them immediately wanted to read other books by Gill Lewis. Because empathy is a thread that runs through much of her work ( Gorilla Dawn , Moon Bear , The Closest Thing to Flying and so on). Thanks to EmpathyLab's lists, I was able to point them in the direction of several other books, by her and others.

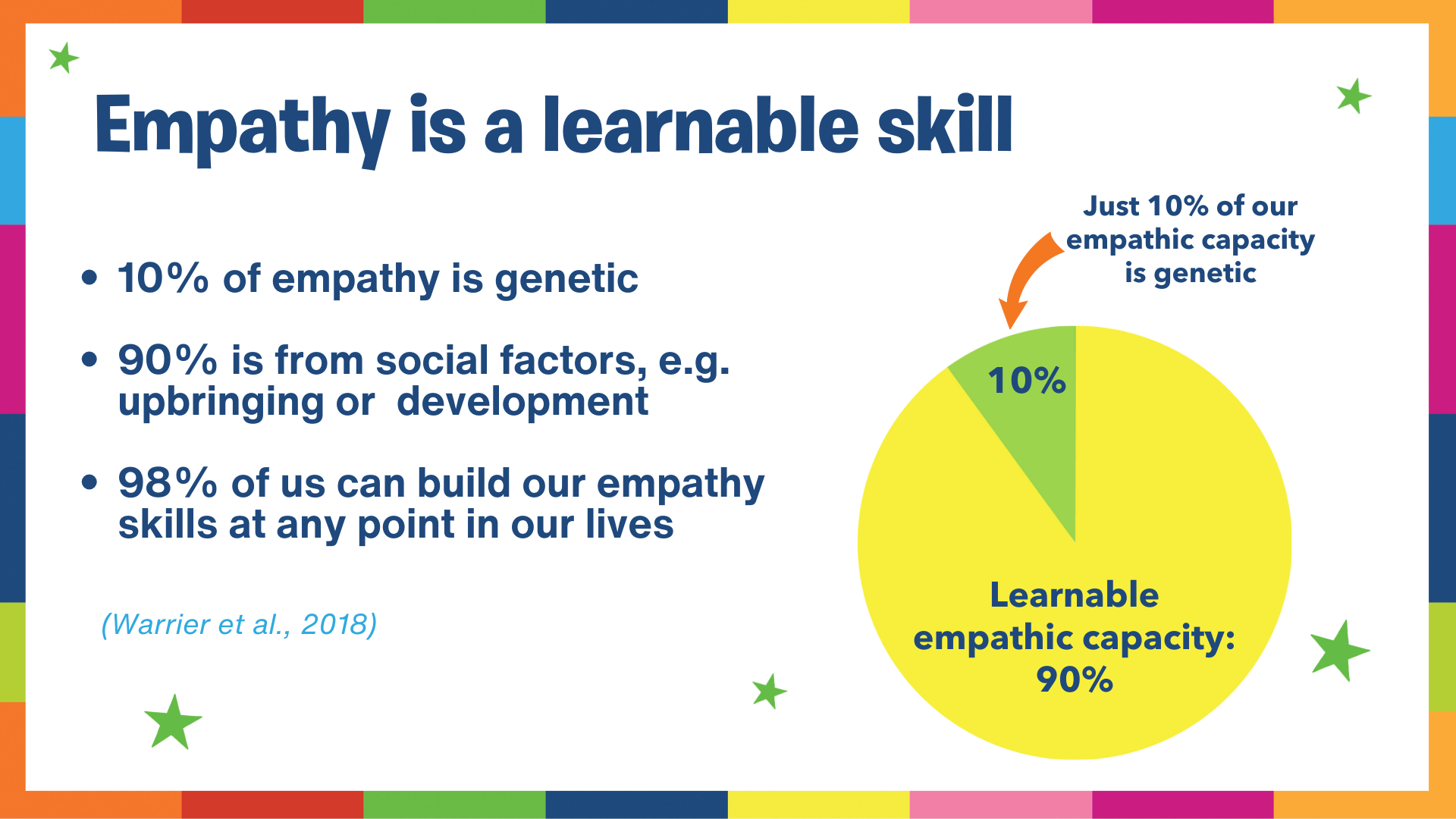

I think we agree that teaching children about empathy and providing them with opportunities to develop it is one of the most important gifts we can give them as adults. The fact that empathy has gone from being something that schools sort of understood a few years ago to being something that has got an increasingly solid evidence base is crucial.

There’s always been anecdotal evidence that reading stories is important for children and that it can change how they think but now that’s backed up with research. The empathy revolution (and it is a revolution) is only going to pick up more momentum over the next few years as the need for it becomes ever more apparent. Working in schools and in the world of children’s books means that we’re in the front line. There’s nowhere else I’d rather be.